By Chidi Odinkalu

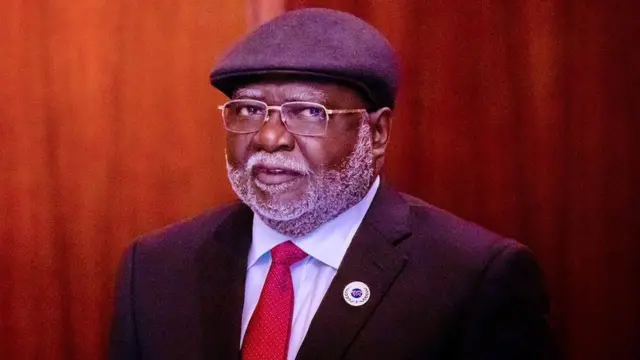

A look at a career marred by white-collar savagery as Olukayode Ariwoola prepares his retirement after years at the top of the Nigerian judiciary.

At the beginning of March 2020, Nigeria’s Supreme Court dismissed an application for the review of its seven-week-old decision to judicially install Hope Uzodinma as the Governor of Imo State, citing as its main reason the need to preserve the authority and finality of decisions of the apex court.

The court issued what appeared to be a principled defence of the finality of its judgments, declaring somewhat ostentatiously that once it had issued a decision, “it shall remain forever.”

Olukayode Ariwoola, who delivered the judgment of the majority in the review, was also a member of the original panel which decided in January 2020 that Mr Uzodinma had won the election despite being the candidate who came fourth in the tally of votes scored among the contestants on the ballot.

Few could recall that Olukayode Ariwoola had previous experience in this improbable judicial alchemy.

Ahead of the 2007 general elections, the then-ruling Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) chose Joy Emordi, a lawyer, to fly its flag in the contest to represent Anambra North in the Senate.

In the contest for the party ticket, she had defeated Ubanese Alphonsus Igbeke, who had been installed by judicial order after the 2003 elections as the member representing Anambra East/Anambra West in the House of Representatives. After losing the senatorial ticket to Ms Emordi, Ubanese Igbeke relocated his party loyalty to the All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP).

Election day was April 28, 2007, and voting took place in the seven LGAs of Anambra North to determine the person representing the constituency in the Senate. At the end of the contest, the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) returned Joy Emordi as the winner.

Five of the losing candidates, including Ubanese Igbeke, lodged petitions to challenge the outcome before the Election Petition Tribunal in Awka, the capital of Anambra State.

On June 14, 2008, the tribunal dismissed the petitions and upheld the return of Senator Emordi.

Eight months later, on February 10, 2009, a Court of Appeal panel comprising Victor Omage, Ladan Tsamiya, and Olukayode Ariwoola as Justices of Appeal dismissed the appeal by one of the candidates, Jessie Balonwu, against the decision of the first instance tribunal, holding in particular that there were elections in the seven Local Government Areas (LGAs) of the constituency.

This was significant because the crux of Ubanese Igbeke’s appeal was that there were no elections in two of the seven LGAs in the constituency, specifically in Anyamelum and Onitsha South, respectively.

At the same time, Igbeke also asked the Court of Appeal to find that Joy Emordi had failed to score the highest number of lawful votes in the election and to, instead, declare that he had scored the highest number of lawful votes in the election and return him as the winner.

One year later, on March 25, 2010, the Court of Appeal comprised Amiru Sanusi, Ladan Tsamiya, and Olukayode Ariwoola found in favour of Ubanese Igbeke on all issues and returned him as duly elected.

To reach this decision, a panel of the Court of Appeal, which included two of the three Justices who decided the earlier case, inexplicably changed their position on the pivotal issue of whether balloting occurred in all the LGAs in the constituency but felt no need to explain how or why.

Having found Igbeke’s favour on that point, the panel incredulously proceeded to award the election to him when the only logical order was a re-run in the LGAs where the court claimed no balloting occurred. The skills required to produce this outcome defied all laws of judicial calisthenics.

Senator Emordi lost in her effort to appeal against this to the Supreme Court. On May 25, 2010 – with a mere one year to spare out of a four-year parliamentary term – Ubanese Igbeke took the oath as Senator representing Anambra North.

Of the three Justices of Appeal who implausibly sent Ubanese Igbeke to the Senate, Ladan Tsamiya remained on the Court of Appeal, where his career ended in ignominy in 2016 on allegations of corruption in another election dispute.

In the month of the fourth anniversary of the senatorial debut of Ubanese Igbeke secured through their judicial machination, Amiru Sanusi proceeded in May 2015 to the Supreme Court, from where he retired in February 2020, the month after they installed Hope Uzodinma as Imo State governor.

The year after Igbeke entered the Senate, in November 2011, Goodluck Jonathan appointed Olukayode Ariwoola as a Justice of the Supreme Court. After over a decade on the court, in June 2022, Ariwoola emerged as chief justice after leading an unprecedented mutiny against his predecessor in which 14 justices accused then-Chief Justice Tanko Muhammad of ignoring their wellbeing. He was officially born on August 22, 1954.

The tenure of Olukayode Ariwoola as chief justice of Nigeria began “amid ‘all-time low’ judicial trust.” It was not too much to hope that shoring up public trust in the judicial branch should have been a priority in these circumstances. Instead, he seemed to be on a mission to make up for lost opportunities in the material benefits of office.

The result was a tenure that denuded public trust in the judiciary rather than rehabilitated it.

As CJN, Olukayode Ariwoola will be well remembered for the alacrity with which he redressed any previous neglect – real or imagined – of the welfare of his own family and his beloved village, Iseyin, in Oyo State.

In two years in the position, he made his son a judge of the Federal High Court, his daughter-in-law a judge of the High Court of the Federal Capital Territory, his brother auditor of the National Judicial Council (NJC) chaired by himself as the chief justice; and another reported member of his family a justice of the Court of Appeal.

It was done with a grubbiness that did not pretend to have any regard for the authority of the CJN or respect for the Judicial Code of Conduct, which explicitly prohibits such manifest nepotism with the warning that a judge “who takes advantage of the judicial office for personal gain or gain by his or her relative or relation abuses power.”

Fittingly, Olukayode Ariwoola’s tenure as chief justice ends in a filigree of clannish patronage. In his last meeting as chair of the NJC, he handed out judicial sinecures to two sisters, one to the High Court of Kwara State and another to the High Court of Ondo State.

The month before, he had installed their brother as a judge of the High Court of the Federal Capital Territory. Their dad was a judicial benefactor.

In 2020, the Legal Practitioners Privileges Committee (LPPC), then chaired by Olukayode’s Ariwoola’s predecessor, sanctioned a lawyer who had applied for elevation to the rank of SAN by altering Supreme Court judgments to insert his name as counsel in cases in which he had not acted.

Twenty-one days before his departure as chief justice, Olukayode Ariwoola rushed through new elevations, making this same lawyer a SAN when he was better off being struck off the roll entirely.

When his successor inaugurates this kind of specimen into the inner bar in one of her first acts as chief justice, it will set the seal on unquestionably the most baleful judicial legacy in contemporary Nigeria.

Addressing the opening of the legal year before a special session of the Supreme Court – the last to be presided over by Olukayode Ariwoola as CJN – in November 2023, Ebun Sofunde, a senior advocate of Nigeria (SAN), speaking on behalf of the Body of Senior Advocates of Nigeria (BOSAN), testified that judicial reputation “is at an all-time low… to a point where it may no longer be redeemable” and ended with the complaint that Supreme Court judgments under him had become “perfunctory.”

These words easily sum up what will be remembered as the most lamentable tenure in the office of the Chief Justice of Nigeria since the appointment of the first indigenous CJN in 1958.

A lawyer and a teacher, Odinkalu can be reached at chidi.odinkalu@tufts.edu